Horseshoe Crab Spawning Season

May 24, 2022

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that it is horseshoe crab spawning season on the shores of Long Island?

Every year during the full and new moon high tides from May through August (depending on latitude) horseshoe crabs make their way to shorelines up and down the eastern coast of the United States to lay their eggs in the sand. Horseshoe crab females can lay up to 88,000 eggs during one spawning period.

Horseshoe crabs have existed relatively unchanged for approximately 445 million years and have survived five mass extinctions. They are not true crabs and are more closely related to spiders and scorpions. They are harmless creatures and their tails or telsons are not used as weapons but rather to help them flip over if they get caught upside down.

There are four surviving species of horseshoe crab; Limulus polyphemus, the Atlantic Horseshoe crab, which can be only found along the eastern coast of the United States, and three other species found in various parts of eastern and southeastern Asia.

Horseshoe crabs are fascinating creatures that have ten eyes and copper-based blue blood. When horseshoe crab blood comes into contact with bacteria, a clot immediately forms around the bacteria. That is why horseshoe crab blood has been used in the biomedical industry for over 30 years to screen for bacteria in every pharmaceutical substance that enters the human body, including vaccines and surgical implants. Horseshoe crab blood has been a key element used during the production of Covid vaccines.

Horseshoe crabs are a keystone species, which means that removing them from their environment would have a drastic effect on the ecosystem in which they exist. This is especially true with regard to the relationship between horseshoe crabs and the migrating shore bird, the rufa red knot. Every year, red knots make a 16,000-mile journey from the tip of South America to their breeding grounds in the arctic. The largest horseshoe crab spawning ground in the US is in Delaware Bay, a key stopover point in the red knot migration route. The red knots stop there to refuel on fatty-rich horseshoe crab eggs.

Although horseshoe crabs have survived this long, man-made pressures threaten their existence. Between 1850 and 1920, horseshoe crabs were harvested and used as fertilizer. They are currently used as bait in the eel and whelk fisheries. Coastal development and shoreline hardening coupled with sea-level-rise is diminishing the range of spawning sites available to horseshoe crabs. It is also estimated that approximately 15% of Atlantic horseshoe crabs die as a result of being bled for biomedical use.

Every year, horseshoe crab spawning surveys are held all over Long Island to determine the status of local horseshoe crab populations and to provide information that will help update regulations for management of the species.

The WaterFront Center in Oyster Bay holds a spawning survey at Beekman and Roosevelt beaches every summer. If you are interested in participating in a horseshoe crab spawning survey on Long Island please visit www.nyhorseshoecrab.org

-Christine Suter

Every year during the full and new moon high tides from May through August (depending on latitude) horseshoe crabs make their way to shorelines up and down the eastern coast of the United States to lay their eggs in the sand. Horseshoe crab females can lay up to 88,000 eggs during one spawning period.

Horseshoe crabs have existed relatively unchanged for approximately 445 million years and have survived five mass extinctions. They are not true crabs and are more closely related to spiders and scorpions. They are harmless creatures and their tails or telsons are not used as weapons but rather to help them flip over if they get caught upside down.

There are four surviving species of horseshoe crab; Limulus polyphemus, the Atlantic Horseshoe crab, which can be only found along the eastern coast of the United States, and three other species found in various parts of eastern and southeastern Asia.

Horseshoe crabs are fascinating creatures that have ten eyes and copper-based blue blood. When horseshoe crab blood comes into contact with bacteria, a clot immediately forms around the bacteria. That is why horseshoe crab blood has been used in the biomedical industry for over 30 years to screen for bacteria in every pharmaceutical substance that enters the human body, including vaccines and surgical implants. Horseshoe crab blood has been a key element used during the production of Covid vaccines.

Horseshoe crabs are a keystone species, which means that removing them from their environment would have a drastic effect on the ecosystem in which they exist. This is especially true with regard to the relationship between horseshoe crabs and the migrating shore bird, the rufa red knot. Every year, red knots make a 16,000-mile journey from the tip of South America to their breeding grounds in the arctic. The largest horseshoe crab spawning ground in the US is in Delaware Bay, a key stopover point in the red knot migration route. The red knots stop there to refuel on fatty-rich horseshoe crab eggs.

Although horseshoe crabs have survived this long, man-made pressures threaten their existence. Between 1850 and 1920, horseshoe crabs were harvested and used as fertilizer. They are currently used as bait in the eel and whelk fisheries. Coastal development and shoreline hardening coupled with sea-level-rise is diminishing the range of spawning sites available to horseshoe crabs. It is also estimated that approximately 15% of Atlantic horseshoe crabs die as a result of being bled for biomedical use.

Every year, horseshoe crab spawning surveys are held all over Long Island to determine the status of local horseshoe crab populations and to provide information that will help update regulations for management of the species.

The WaterFront Center in Oyster Bay holds a spawning survey at Beekman and Roosevelt beaches every summer. If you are interested in participating in a horseshoe crab spawning survey on Long Island please visit www.nyhorseshoecrab.org

-Christine Suter

Oyster Shell Tabby on the Historic

Oyster Bay Railroad Station

May 10, 2022

Image Credits: Christine Suter

Did you know the upper façade of the historic Oyster Bay Railroad Station is plastered with an oyster shell stucco called tabby?

Tabby, sometimes called coastal concrete, is made by burning oyster shells to create lime. The lime is then mixed with water, sand, and broken oyster shells. Tabby was originally used by Spanish settlers in North Carolina and Florida in the mid to late 1500s and then by British colonists in South Carolina and Georgia circa 1700. Most tabby structures exist along the southern coast of the U.S. but some can be found as far north as New York.

The original railroad station was built by the Long Island Railroad in 1889. After Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, the building was redesigned and expanded by railroad architect Bradford Lee Gilbert in 1902 to accommodate an expected increase in visitors to Oyster Bay. The tabby was not added to the facade until the redesign in 1902. It is believed that Gilbert added the oyster shell stucco in recognition of the town’s namesake.

The Oyster Bay Station building is home to the Oyster Bay Railroad Museum. The building will be open to the public in June. If you are visiting the Railroad Museum, be sure to take a close look at the western facing side of the of the building and you will be able to see the oyster shells. Unlike most oyster shell tabby which is rough-looking and made using fragments of oyster shells, Gilbert used a large number of oyster shell halves on the station’s façade giving it a more attractive finish.

During the building’s most recent restoration which began in 2016, the Railroad Museum’s Preservation Consultant, John Collins, collected additional oyster shells by hand from a Bayville beach to replace shells in areas where the stucco had been removed or worn away over time.

- Christine Suter

Tabby, sometimes called coastal concrete, is made by burning oyster shells to create lime. The lime is then mixed with water, sand, and broken oyster shells. Tabby was originally used by Spanish settlers in North Carolina and Florida in the mid to late 1500s and then by British colonists in South Carolina and Georgia circa 1700. Most tabby structures exist along the southern coast of the U.S. but some can be found as far north as New York.

The original railroad station was built by the Long Island Railroad in 1889. After Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901, the building was redesigned and expanded by railroad architect Bradford Lee Gilbert in 1902 to accommodate an expected increase in visitors to Oyster Bay. The tabby was not added to the facade until the redesign in 1902. It is believed that Gilbert added the oyster shell stucco in recognition of the town’s namesake.

The Oyster Bay Station building is home to the Oyster Bay Railroad Museum. The building will be open to the public in June. If you are visiting the Railroad Museum, be sure to take a close look at the western facing side of the of the building and you will be able to see the oyster shells. Unlike most oyster shell tabby which is rough-looking and made using fragments of oyster shells, Gilbert used a large number of oyster shell halves on the station’s façade giving it a more attractive finish.

During the building’s most recent restoration which began in 2016, the Railroad Museum’s Preservation Consultant, John Collins, collected additional oyster shells by hand from a Bayville beach to replace shells in areas where the stucco had been removed or worn away over time.

- Christine Suter

Why Seaweed Has Different Colors

April 18, 2022

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that a seaweed’s color is determined by how deep it grows in the water? Seaweeds are classified as either green, brown or red and contain photosynthetic pigments that absorb different color wavelengths of light. As sunlight passes though the water column, various color wavelengths are filtered out at different depths. Red wavelengths are filtered out closer to the surface while blue and green wavelengths penetrate deeper. We see color based on the wavelengths that are being reflected and not absorbed by the seaweed.

Similar to land plants, green seaweed contains mostly chlorophyll pigments which absorb red light and reflect green and blue light. Because of this, green seaweed is found growing closer to the surface of the water where red light is more abundant. Brown seaweed grows in the middle of the water column and contains some chlorophyll but mainly relies on a pigment called fucoxanthin, which reflects yellow light. Red seaweed also contains chlorophyll but mostly relies on a bluish pigment called phycocyanin and a reddish pigment called phycoerythrin. This combination of pigments allows red seaweed to absorb deep-penetrating blue light wavelengths and grow at greater depths than green and brown seaweed.

You can find all three colored seaweeds floating in and around Oyster Bay and Cold Spring Harbor.

- Christine Suter

Similar to land plants, green seaweed contains mostly chlorophyll pigments which absorb red light and reflect green and blue light. Because of this, green seaweed is found growing closer to the surface of the water where red light is more abundant. Brown seaweed grows in the middle of the water column and contains some chlorophyll but mainly relies on a pigment called fucoxanthin, which reflects yellow light. Red seaweed also contains chlorophyll but mostly relies on a bluish pigment called phycocyanin and a reddish pigment called phycoerythrin. This combination of pigments allows red seaweed to absorb deep-penetrating blue light wavelengths and grow at greater depths than green and brown seaweed.

You can find all three colored seaweeds floating in and around Oyster Bay and Cold Spring Harbor.

- Christine Suter

Raingardens

April 12, 2022

Image Credit: Heather Johnson

Did you know that raingardens can help improve water quality in nearby bodies of water by cleansing polluted stormwater runoff?

Runoff from impervious surfaces in urban and suburban areas contains oils, trace metals and chemicals that can wreak havoc on the marine environment.

A raingarden is a type of green infrastructure basin that can be installed in either a community or residential setting and used to capture and filter stormwater runoff. They are typically constructed using native plants and layers of mulch and permeable soil. In a community setting a raingarden is usually installed on or at the bottom of a sloped area where it can capture runoff from surrounding impervious surfaces. In a residential setting a raingarden is most commonly installed at the base of a downspout.

If designed properly, raingardens can be effective at removing up to 90% of chemicals from stormwater runoff and can absorb runoff as much as 30% to 40% more efficiently than a typical lawn. In addition to providing filtration, raingardens can recharge groundwater, mitigate flooding and prevent runoff from inundating storm sewers. The benefit of using native plants is that they do not require fertilization and they provide a habitat for bees, butterflies and other pollinators.

Last October, Friends of the Bay installed two raingardens along the Western Waterfront in Oyster Bay. The Western Waterfront Raingarden Project was made possible by a grant from the Long Island Sound Stewardship Fund at the Long Island Community Foundation.

- Christine Suter

Runoff from impervious surfaces in urban and suburban areas contains oils, trace metals and chemicals that can wreak havoc on the marine environment.

A raingarden is a type of green infrastructure basin that can be installed in either a community or residential setting and used to capture and filter stormwater runoff. They are typically constructed using native plants and layers of mulch and permeable soil. In a community setting a raingarden is usually installed on or at the bottom of a sloped area where it can capture runoff from surrounding impervious surfaces. In a residential setting a raingarden is most commonly installed at the base of a downspout.

If designed properly, raingardens can be effective at removing up to 90% of chemicals from stormwater runoff and can absorb runoff as much as 30% to 40% more efficiently than a typical lawn. In addition to providing filtration, raingardens can recharge groundwater, mitigate flooding and prevent runoff from inundating storm sewers. The benefit of using native plants is that they do not require fertilization and they provide a habitat for bees, butterflies and other pollinators.

Last October, Friends of the Bay installed two raingardens along the Western Waterfront in Oyster Bay. The Western Waterfront Raingarden Project was made possible by a grant from the Long Island Sound Stewardship Fund at the Long Island Community Foundation.

- Christine Suter

Fertilizer Helps Fuel Harmful Algal Blooms

April 6, 2022

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that fertilizing your lawn can help fuel harmful algal blooms in our local waterways?

Fertilizers contain high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus. These are two nutrients that encourage grass to grow, but they are the are also the same two nutrients that stimulate the growth of phytoplankton, the aquatic organisms that form algal blooms.

Rain and runoff carry fertilizer from your lawn into nearby ponds, lakes and waterways. This can lead to eutrophication, or the excess buildup of nutrients in a body of water. Eutrophication is what causes an overgrowth of phytoplankton and can often lead to harmful algal blooms. Some species of phytoplankton produce natural toxins and in abundance they can cause harm to other organisms including pets and humans.

If you chose to fertilize your lawn this spring, there are several resources available to help guide you through the process and ensure that you are doing it in the most environmentally friendly way possible. The following two websites run by the EPA and the DEC, offer tips for fertilizing your lawn as well as for stormwater management on your property:

https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/what-you-can-do-your-yard

https://www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/67239.html

The following PDF was crated by the Long Island Nitrogen Action Plan (LINAP):

https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/water_pdf/linapfertilizer.pdf

- Christine Suter

Fertilizers contain high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus. These are two nutrients that encourage grass to grow, but they are the are also the same two nutrients that stimulate the growth of phytoplankton, the aquatic organisms that form algal blooms.

Rain and runoff carry fertilizer from your lawn into nearby ponds, lakes and waterways. This can lead to eutrophication, or the excess buildup of nutrients in a body of water. Eutrophication is what causes an overgrowth of phytoplankton and can often lead to harmful algal blooms. Some species of phytoplankton produce natural toxins and in abundance they can cause harm to other organisms including pets and humans.

If you chose to fertilize your lawn this spring, there are several resources available to help guide you through the process and ensure that you are doing it in the most environmentally friendly way possible. The following two websites run by the EPA and the DEC, offer tips for fertilizing your lawn as well as for stormwater management on your property:

https://www.epa.gov/nutrientpollution/what-you-can-do-your-yard

https://www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/67239.html

The following PDF was crated by the Long Island Nitrogen Action Plan (LINAP):

https://www.dec.ny.gov/docs/water_pdf/linapfertilizer.pdf

- Christine Suter

Ospreys Return to Long Island in the Spring

April 1, 2022

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that ospreys start returning to Long Island for their breeding season around this time of year?

The osprey, also known as a sea hawk or fish hawk, preys almost exclusively on fish and prefers to nest in high places near the water. Historically ospreys nested in tall trees but now they also nest on utility poles and nesting platforms that have been constructed by conservation groups.

The ospreys found on Long Island spend the winter in South America, while some stay in the southernmost part of the United States, and they return to their northern nesting grounds in early to mid-March. Ospreys mate for life and like most birds of prey, the female is larger than the male. Osprey pairs usually return to the same nest every year and the male will arrive early to defend the nesting site. The female will lay up to three eggs a few weeks after arriving at the nest and the eggs will hatch five to six weeks later. Most ospreys will return south by the end of October.

During the 1950s and 60s, osprey numbers were in drastic decline due to the harmful effects of the pesticide DDT. DDT affected the birds’ calcium production and as a result they produced eggs with shells that would easily break. The use of DDT was banned in 1972 and consequently osprey populations have rebounded over the past 50 years.

Ospreys are currently not threatened or endangered, but they are protected under the Federal Migratory Bird Act which is regulated by the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service.

Ospreys have a distinct high-pitched call and will become very vocal if they feel you are encroaching on their territory. You may not even be aware that you are near a nesting site when an osprey will alert you to its presence. Keep a look out and an ear open for ospreys this summer.

There are numerous osprey nests in the Oyster Bay area and there is even a live osprey cam of a nest in Oyster Bay hosted by PSEG Long Island that you can access by visiting https://www.psegliny.com/wildlife/ospreycam

- Christine Suter

The osprey, also known as a sea hawk or fish hawk, preys almost exclusively on fish and prefers to nest in high places near the water. Historically ospreys nested in tall trees but now they also nest on utility poles and nesting platforms that have been constructed by conservation groups.

The ospreys found on Long Island spend the winter in South America, while some stay in the southernmost part of the United States, and they return to their northern nesting grounds in early to mid-March. Ospreys mate for life and like most birds of prey, the female is larger than the male. Osprey pairs usually return to the same nest every year and the male will arrive early to defend the nesting site. The female will lay up to three eggs a few weeks after arriving at the nest and the eggs will hatch five to six weeks later. Most ospreys will return south by the end of October.

During the 1950s and 60s, osprey numbers were in drastic decline due to the harmful effects of the pesticide DDT. DDT affected the birds’ calcium production and as a result they produced eggs with shells that would easily break. The use of DDT was banned in 1972 and consequently osprey populations have rebounded over the past 50 years.

Ospreys are currently not threatened or endangered, but they are protected under the Federal Migratory Bird Act which is regulated by the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service.

Ospreys have a distinct high-pitched call and will become very vocal if they feel you are encroaching on their territory. You may not even be aware that you are near a nesting site when an osprey will alert you to its presence. Keep a look out and an ear open for ospreys this summer.

There are numerous osprey nests in the Oyster Bay area and there is even a live osprey cam of a nest in Oyster Bay hosted by PSEG Long Island that you can access by visiting https://www.psegliny.com/wildlife/ospreycam

- Christine Suter

Lester Wolff National Wildlife Refuge

(Formerly the Oyster Bay National Wildlife Refuge)

March 26, 2022

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that the Oyster Bay refuge, now officially known as the Lester Wolff National Wildlife Refuge (LWNWR), is the largest in the Long Island National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) Complex?

Established as a NWR in 1968, it is one of the only bay bottom refuges owned by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and has been designated by the State of New York as a Significant Coastal Fish and Wildlife Habitat.

The refuge consists of 3,209 acres of bay bottom, which makes up 78% of the refuge, in addition to coastal salt marsh and freshwater wetland. It is home to an abundance of wildlife including birds, reptiles, marine invertebrates, fish, and shellfish.

More than 126 bird species have been observed in the LWNWR, including several species of raptor, shorebirds, gulls, terns and 23 species of waterfowl, many of which spend the winter here before migrating to their northern breeding grounds in the summer. The LWNWR is known to have the most intense winter waterfowl use of any of the Long Island NWRs.

In addition to many bird species, harbor seals have been observed at the mouth of Oyster Bay during the winter months, and the refuge contains one of the largest populations of northern diamondback terrapins on Long Island. The terrapins make their nests along the marshy coastlands or the sands of Centre Island Beach in the summer and can often be spotted near the coastline poking their heads above the water.

- Christine Suter

Established as a NWR in 1968, it is one of the only bay bottom refuges owned by the US Fish and Wildlife Service and has been designated by the State of New York as a Significant Coastal Fish and Wildlife Habitat.

The refuge consists of 3,209 acres of bay bottom, which makes up 78% of the refuge, in addition to coastal salt marsh and freshwater wetland. It is home to an abundance of wildlife including birds, reptiles, marine invertebrates, fish, and shellfish.

More than 126 bird species have been observed in the LWNWR, including several species of raptor, shorebirds, gulls, terns and 23 species of waterfowl, many of which spend the winter here before migrating to their northern breeding grounds in the summer. The LWNWR is known to have the most intense winter waterfowl use of any of the Long Island NWRs.

In addition to many bird species, harbor seals have been observed at the mouth of Oyster Bay during the winter months, and the refuge contains one of the largest populations of northern diamondback terrapins on Long Island. The terrapins make their nests along the marshy coastlands or the sands of Centre Island Beach in the summer and can often be spotted near the coastline poking their heads above the water.

- Christine Suter

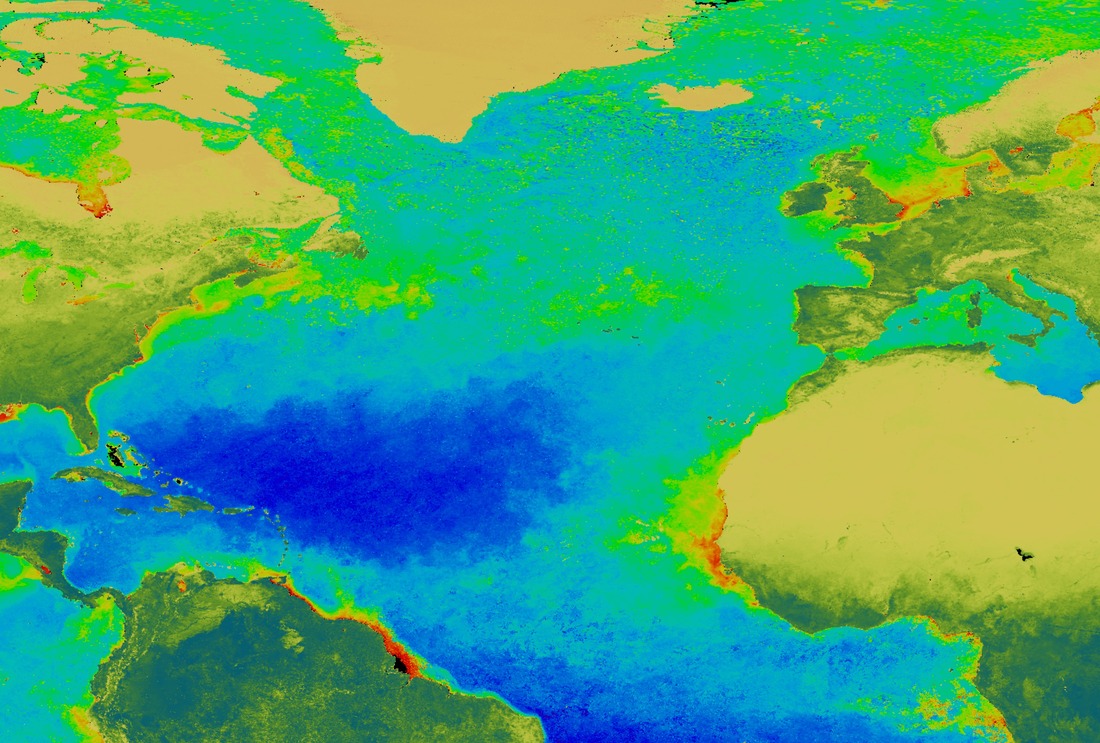

Spring Phytoplankton Bloom

March 23, 2022

Image Credit: Stuart A. Snodgrass & NOAA

As winter turns to spring we are aware of terrestrial flowers that begin to bloom, but did you know that there is also a bloom that takes place in the North Atlantic Ocean? The North Atlantic spring bloom refers to a phytoplankton bloom that occurs every year in the early spring and can last into late spring, early summer. It is the largest, annually occurring bloom in the world.

Phytoplankton are microscopic marine algae that, like terrestrial plants, contain chlorophyll and require sunlight and nutrients to grow. A bloom occurs when there is rapid growth and accumulation of phytoplankton. Most people are familiar with the term “harmful agal bloom,” which refers to when certain species of phytoplankton with harmful characteristics bloom out of control and cause detrimental effects to wildlife and humans. This is not necessarily the case with the North Atlantic spring bloom.

Certain conditions come into play in the early spring that cause the spring bloom to occur. During the winter, the cold weather and strong winds causes a lot of mixing in the water column and stirs up nutrients from the ocean bottom. When winter turns to spring and the temperature warms it causes stratification in the water column. This means that the water becomes layered are there is less mixing between the warmer surface layer and colder deep water. Nutrients gets trapped in the surface layer and as the days get longer the surface layer also receive more sunlight. Phytoplankton exploit the conditions of high nutrient levels and increased sunlight to proliferate. Over time the nutrients become depleted and the bloom dies down.

- Christine Suter

Phytoplankton are microscopic marine algae that, like terrestrial plants, contain chlorophyll and require sunlight and nutrients to grow. A bloom occurs when there is rapid growth and accumulation of phytoplankton. Most people are familiar with the term “harmful agal bloom,” which refers to when certain species of phytoplankton with harmful characteristics bloom out of control and cause detrimental effects to wildlife and humans. This is not necessarily the case with the North Atlantic spring bloom.

Certain conditions come into play in the early spring that cause the spring bloom to occur. During the winter, the cold weather and strong winds causes a lot of mixing in the water column and stirs up nutrients from the ocean bottom. When winter turns to spring and the temperature warms it causes stratification in the water column. This means that the water becomes layered are there is less mixing between the warmer surface layer and colder deep water. Nutrients gets trapped in the surface layer and as the days get longer the surface layer also receive more sunlight. Phytoplankton exploit the conditions of high nutrient levels and increased sunlight to proliferate. Over time the nutrients become depleted and the bloom dies down.

- Christine Suter

Wetlands Store Carbon

March 16, 2022

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that wetlands store an enormous amount of carbon?

The global estimate of total carbon storage by wetlands is approximately 225 billion metric tons. That’s roughly equivalent to carbon emissions from 189 million cars a year.

Wetland soils are water-logged and oxygen poor which slows down decomposition and leads to the accumulation of organic matter in the soil. Carbon makes up approximately 50 percent of the organic matter that is stored.

Wetland plants absorb carbon from the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide and convert it into organic compounds through the process of photosynthesis. The carbon is then stored in the plant biomass and in the soil.

Salt marshes, seagrass beds, mangroves and other types of tidal wetlands sequester carbon at rates up to 10 times greater than forests.

That’s why wetlands and wetland restoration are increasingly important with regard to reducing the impacts of climate change on our planet.

-Christine Suter

The global estimate of total carbon storage by wetlands is approximately 225 billion metric tons. That’s roughly equivalent to carbon emissions from 189 million cars a year.

Wetland soils are water-logged and oxygen poor which slows down decomposition and leads to the accumulation of organic matter in the soil. Carbon makes up approximately 50 percent of the organic matter that is stored.

Wetland plants absorb carbon from the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide and convert it into organic compounds through the process of photosynthesis. The carbon is then stored in the plant biomass and in the soil.

Salt marshes, seagrass beds, mangroves and other types of tidal wetlands sequester carbon at rates up to 10 times greater than forests.

That’s why wetlands and wetland restoration are increasingly important with regard to reducing the impacts of climate change on our planet.

-Christine Suter

Sugar Kelp

March 11, 2022

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that growing sugar kelp in local waters can provide environmental, nutritional, commercial and economic benefits?

Sugar kelp is a sustainable aquaculture crop that can be grown during the winter, support jobs in the local community, and can be cultivated in the same areas leased by shellfish growers. It requires no chemicals or fertilizer to grow and provides important ecosystem services including the removal of excess nutrients from the water through a process known as bioextraction. Once the kelp is harvested, it can be used as a food source, a fertilizer, to make packaging materials and as an ingredient in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

Friends of the Bay is currently cultivating two kelp lines in Oyster Bay in a project supported by The Moore Family Charitable Foundation and their Lazy Point Farms LLC.

-Christine Suter

Sugar kelp is a sustainable aquaculture crop that can be grown during the winter, support jobs in the local community, and can be cultivated in the same areas leased by shellfish growers. It requires no chemicals or fertilizer to grow and provides important ecosystem services including the removal of excess nutrients from the water through a process known as bioextraction. Once the kelp is harvested, it can be used as a food source, a fertilizer, to make packaging materials and as an ingredient in cosmetics and pharmaceuticals.

Friends of the Bay is currently cultivating two kelp lines in Oyster Bay in a project supported by The Moore Family Charitable Foundation and their Lazy Point Farms LLC.

-Christine Suter

Winter Ducks in Oyster Bay

March 3, 2022

Did you know that a variety of duck species use Oyster Bay as their winter home before migrating to their northern breeding grounds in the summer?

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Oyster Bay National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) has the “heaviest winter waterfowl use of any of the Long Island NWRs."

The most common winter waterfowl found in Oyster Bay are the greater scaup, bufflehead, and black duck. These three species account for approximately 85% of all ducks that use the refuge with the greater scaup making up more than half of ducks that use the refuge.

Other winter ducks that appear in Oyster Bay NWR are long-tailed ducks, American widgeons, gadwalls, green-winged teals, red-breasted mergansers, and common goldeneyes.

-Christine Suter

According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Oyster Bay National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) has the “heaviest winter waterfowl use of any of the Long Island NWRs."

The most common winter waterfowl found in Oyster Bay are the greater scaup, bufflehead, and black duck. These three species account for approximately 85% of all ducks that use the refuge with the greater scaup making up more than half of ducks that use the refuge.

Other winter ducks that appear in Oyster Bay NWR are long-tailed ducks, American widgeons, gadwalls, green-winged teals, red-breasted mergansers, and common goldeneyes.

-Christine Suter

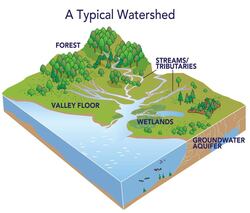

About Watersheds

Image Credit: nurturenaturecenter.org

Did you know that the word WATERSHED refers to "a land area that channels rainwater and snowmelt to creeks streams and rivers, and eventually to outflow points such as reservoirs bays and the ocean?" - (oceanservice.noaa.gov)

When rain falls, the water can take several paths. It is either absorbed by the land and will eventually seep into the nearest stream--some water penetrates even deeper into reservoirs called aquifers--or it flows over land into the nearest stream or river, and ultimately to the bay or ocean.

It is important to monitor stormwater runoff within a watershed because water picks up chemical and solid pollutants as it flows from upland to its final destination in coastal waterways.

Friends of the Bay’s mission is to protect and restore the ecological integrity and productivity of the Oyster Bay Cold/ Spring Harbor Estuary and the surrounding watershed. This includes all the waterways within the boundaries outlined on the attached map.

- Christine Suter

When rain falls, the water can take several paths. It is either absorbed by the land and will eventually seep into the nearest stream--some water penetrates even deeper into reservoirs called aquifers--or it flows over land into the nearest stream or river, and ultimately to the bay or ocean.

It is important to monitor stormwater runoff within a watershed because water picks up chemical and solid pollutants as it flows from upland to its final destination in coastal waterways.

Friends of the Bay’s mission is to protect and restore the ecological integrity and productivity of the Oyster Bay Cold/ Spring Harbor Estuary and the surrounding watershed. This includes all the waterways within the boundaries outlined on the attached map.

- Christine Suter

Whelk Egg Casings

Image Credit: Christine Suter

Did you know that this strange snakelike object is a whelk egg casing? Whelks are large carnivorous snails found in the marine environment. The knobbed whelk and channeled whelk are the most common types of whelks found in our area.

Whelk eggs are fertilized internally and then expelled from the whelk in a string of connected capsules (like the one shown). On average these strings are usually between 1 and 3 feet long, contain 40 to 175 capsules, and each capsule can contain up to 100 eggs! The mother whelk anchors this egg casing to the sea floor so that it doesn’t wash ashore and dry out. Only about 1% of the eggs hatch, but if they emerge successfully, they are 2-4mm in length and can live up to 10 or 15 years.

- Christine Suter

Whelk eggs are fertilized internally and then expelled from the whelk in a string of connected capsules (like the one shown). On average these strings are usually between 1 and 3 feet long, contain 40 to 175 capsules, and each capsule can contain up to 100 eggs! The mother whelk anchors this egg casing to the sea floor so that it doesn’t wash ashore and dry out. Only about 1% of the eggs hatch, but if they emerge successfully, they are 2-4mm in length and can live up to 10 or 15 years.

- Christine Suter

|

© Friends of the Bay. All rights reserved.

|